INNOVATION STORIES

PERFORMANCE MATERIALS

Functional films indispensable for displays

A history of overcoming crises with the underlying strength and

revolutionary ideas of our employees and customers

- INDEX

Even if you are at a disadvantage for a long time, you can turn the tables when the rules change, provided you can quickly notice the change and take action. Our TAC films were no exception. They evolved from the base (support medium) for photographic films, which was a low-profile material, into materials indispensable for liquid crystal displays (LCDs).

LCDs are widely used as screens for common devices such as TVs, notebook computers, and smartphones. In these, liquid crystals are sandwiched by glass substrates, polarizers and many layers of films. Our main products in the performance materials business are plain TAC films, which are protective films for polarizers, and films for wide view, which incorporate optical functions. We now have deep business ties with customers through our products in multiple fields, ties that were established through daily struggles amid crises with our business survival at stake, while taking advantage of growth opportunities.

A challenge starting from a low-profile but crucial product

TAC is a type of resin called cellulose acetate, made using substances derived from plants. TAC is characterized by a low environmental impact, resistance to ultraviolet rays, resistance to decomposition at high temperatures, and resistance to chemical corrosion. This material started to be used in the 1950s as the base for photographic films instead of celluloid, which was highly inflammable.

To produce the finished photographic film, a TAC film was coated by more than a dozen layers of a photosensitive material called an “emulsion” at a time. It was difficult for competitors to enter the market because of high engineering hurdles, and so there were only four photographic film manufacturers in the world. In the 1990s, the photography business, with which Konica was founded, was one of our main business. The crux of the technology was emulsion coating. Although TAC film technology and production were low-profile, engineers took as strong pride in their work as that of coating engineers and continued to optimize the quality and durability.

Demand for photographic films soared as cameras were increasingly purchased by ordinary households. However, a major turning point came in the mid-1990s when digital cameras were released: analog cameras were expected to be replaced by digital ones. And if films were no longer necessary to take photos, would the technologies refined through the development of TAC become obsolete?

The TAC film engineers took action. In those days, LCDs started to be widely used instead of cathode-ray tubes. The engineers learned that TAC films could be applied as protective films for polarizers, and so approached polarizer manufacturers to encourage them to use our TAC films.

The effort bore fruit. Our TAC films gained a new lease of life as optical films for LCD panels. Much higher quality was needed than for the base for photographic films. Although there were difficulties setting up a plant, a new production line started operation at the Kobe site in 2000. At that time, few employees fully realized that our photographic film business would come to an end in only six years.

Turning disadvantages into advantages in a new setting

The TAC films were launched as a new business, but the start was not particularly promising and it was difficult to generate stable profits. Faced with this, the engineers took on two challenges to discover new value of TAC films as optical films.

The first challenge was to reduce the film thickness. While the TAC films for photographic films were 120 μm (0.12 mm) thick, those for LCD polarizers were 80 μm (0.08 mm), just two thirds as thick. However, in the notebook computer market which was starting to grow at that time, the trend was for thinner products, so making the TAC films for polarizers even thinner was expected to yield business opportunities. The engineers aimed to create a thin film of just 40 μm (0.04 mm).

We had a significant advantage in forming thin films: our proprietary film-casting method.

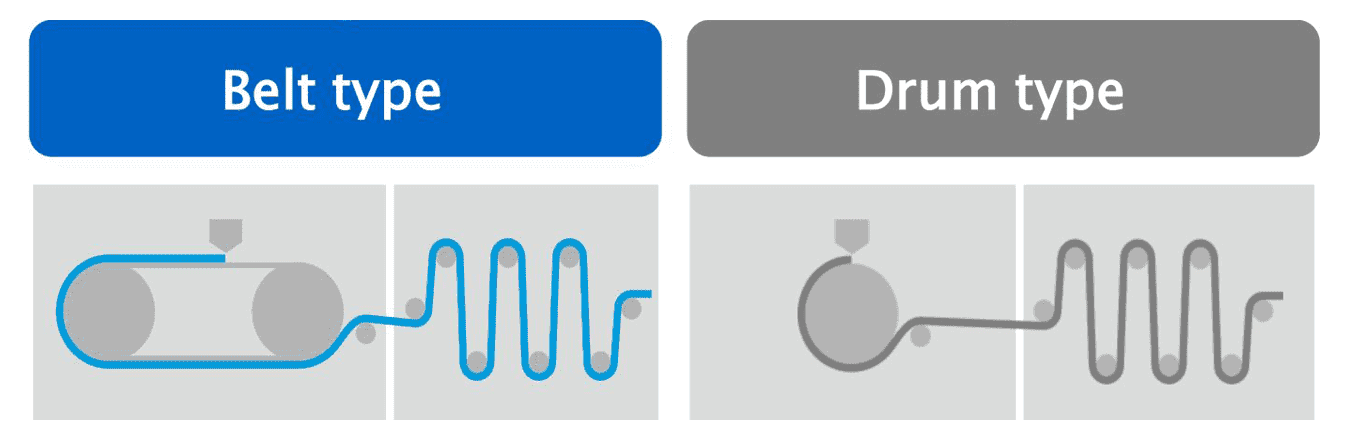

There are two main film-casting methods for TAC films. One is to use solvents, and the other is to use heat, to dissolve the TAC raw material. Regarding the film-casting method using solvents (solution casting), there are two methods depending on the base material for turning liquid into films: the belt type and the drum type. We chose belt-type solution casting to manufacture photographic films. Although it was inferior to the drum type in terms of productivity, it turned out to be superior for forming thin films. We were the only company in the world that could manufacture optical films that were only 40 μm thick because we had continued to refine our belt-type solution casting technology. Later, we continued to lead the market in reducing film thickness, and today, we ship 20 μm (0.02 mm) products for mobile devices.

The success of the TAC film production catapulted the development team into a business group with outstanding engineering capabilities.

The creation of a thin film helped expand new sales channels, but it could not yet produce steady profits. Meanwhile, a project to construct a second production line was already under way next to the existing production line at the Kobe site in anticipation of increased sales, with operation scheduled to start in 2002. The business was likely to be shut down if profits could not cover the investment.

A new era cannot be opened without challengers

We sought to develop high-value-added products that could earn higher profits. The second challenge was to develop films for wide viewing angle—a market that was already dominated by a competitor. These films were designed to make the LCD image viewed from an oblique angle as bright and vivid as when viewed from the front by adding an optical function called “retardation” to TAC films. Developing such a film was very difficult for a latecomer, and almost two years passed by without gaining a foothold in the market.

But there were two opportunities. First, the R&D team came across in-house personnel working on other things that had remained obscure and their technologies. Combinations of technologies and innovative ideas turned these into value. The second opportunity was when the R&D team found new customers by contacting companies beyond the existing supply chain to expand sales, rather than focusing on customers who directly purchased our films.

One day, when the sales and R&D members were visiting a customer together, they learned that vertical alignment (VA) LCDs, which were different from the mainstream driving method at that time, were expected to be applied to LCD TVs due to their superb image quality. They also learned that complex film lamination, which was required for wide viewing angle, was a major issue for mass production. They thought that films for wide viewing angle, which in-house members were struggling to develop, could be developed quickly in-house for VA displays and that customers would be able to handle such films in simple processes by combining various unused in-house technologies with new ideas. These two opportunities led to a breakthrough. It was quickly decided to incorporate a new process into the second production line for TAC, which was already under construction. The plant was redesigned to manufacture films for wide view for VA displays.

In 2003, a VA-TAC film for wide view was developed by integrating a film for wide view with a protective film for polarizers. A Taiwanese LCD panel manufacturer was the first to use the product, and then served as an intermediary to do business with an emerging Taiwanese polarizer manufacturer. In those days, Japan dominated the LCD market, and the Taiwanese companies were challengers. No matter how sophisticated a product is, it cannot be commercially successful without companies that are willing to try the product. VA displays, which attracted much public attention, later became the mainstream of LCD TVs. The manufacturers that used our product grew rapidly, and so did our market share.

The TAC film business started to generate stable profits at last. The integration of a film for wide view with a protective film for polarizers helped avoid the high cost of laminating expensive, complicated films and removed the barrier to larger displays. Without doubt, our product significantly contributed to the widespread use of large LCD TVs.

Offering value that meets modern needs based on communication with customers

The competitor struck back in various ways. In response, when developing the second-generation VA-TAC, we pursued high performance and low cost by reducing the thickness from 80 μm to 40 μm, which was equivalent to the thickness of the protective films used for notebook computers. However, our film for large LCD TVs was too soft and flimsy because of the thinness. Manufacturers of polarizers and final products told us that it was difficult to neatly apply the film to polarizer glass panels because the film was too thin. We therefore contacted a manufacturer of polarizer application equipment, conducted demonstration tests to learn how to ensure proper application, and then made proposals to manufacturers of final products. We were able to gain the trust of customers thanks to our commitment to creating new value for customers through collaboration among the development, production, and sales teams.

For several years around 2005, we had to make difficult but bold investment decisions each year in response to the rapidly growing display market. We were able to manufacture photographic films as finished products in-house. For TAC films, however, we had to manage the chemical plant at the pace of customers in the electrical machinery industry, predict demand, build strong relationships with customers, and meet demand in two to three years. The investment amount was more than half of the annual revenues from this business at that time.

The production processes at customers changed in the late 2010s. In some cases, the manufacturing process was not completed in a single plant, and bare panels had to be transported by sea, causing the film to absorb moisture leading to the problem of changes in the optical characteristics. The weakness of TAC emerged as a problem, and the team members were told that it was theoretically impossible to make the film water-resistant because TAC-based materials were hydrophilic. Nevertheless, they did not give up and applied their knowledge in chemistry, finally identifying an optically effective additive even in hydrophilic material to solve the problem. Today, that film is the main product of the business. Without the desperate struggle, the business might have been shut down. During the transition period in the development, the sales staff did their best to improve the relationships with customers in particular.

Faced with such crises, the team members were concurrently working on developing a new cyclic olefin polymer (COP) by utilizing belt casting technology, which offers superb water resistance, in anticipation of future business. The new COP can be used to create wide and long rolls, which was impossible using TAC or existing COP, by combining our production technologies with new processes and ideas. It is expected to make the polarizer manufacturing process more efficient.

Recently, the focus has been shifting from the engineering aspects, such as film performance and quality, to social issues, such as minimizing the environmental impact in the production process. Meanwhile, preparations have been made to cope with future issues, such as reforming customers’ production processes by offering wider and longer rolls and developing new-generation TAC derived from biomass.

Our business starts by communicating with customers to identify their needs in order to produce designs and develop products that customers have not come up with. To create value, we focus on difficulties faced by competitors but that customers hope to address. To overcome crises, we are committed to this policy.

Our strength lies in our overall capabilities, not individual special technologies. We have overcome our weaknesses with revolutionary ideas. Having been helped by customers who were challengers, we must also continue to take on challenges. This mindset drives our growth.

In the interest of clarity, “Konica” and “Minolta,”—the trade names that were used before the merger that formed “Konica Minolta”—are used throughout this text. Each company underwent a number of name changes throughout their history.